Day 54: Hester's Easy

My AP students have spent the last three weeks reading Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter. Last year, I think I sold this book poorly; we skipped chapters, and my primary selling point was that most high schoolers read it so the students will have common background knowledge with other students when they get to college. Part of the problem was that I had bad memories reading it in high school, so I had a hard time convincing myself it was worthwhile...but after rereading it last year with the students I gained a much greater appreciation for Hawthorne's style of writing and how much this novel can teach my students, and was actually looking forward to teaching it this year.

Instead of linking the novel with The Crucible like I did last year because of the historical setting, the students read and discussed Francine Prose's essay, "I Know Why the Caged Bird Cannot Read" (Harper's Magazine, 1999). Prose decries the practice of teaching what she perceives to be "simplistic" or "easy" texts to English students, books that have characters that are easy to identify with or that only teach morals, books that have value because the author is black, or grew up poor, etc. rather than for the writing itself. She succinctly writes, "Given the fact that these early encounters with literature [in high school English classrooms] leave such indelible impressions, it would seem doubly important to make sure that high school students are actually reading literature. Yet every opportunity to instill adolescents with a lifelong affinity for narrative, for the ways in which the vision of an artist can percolate through an idiosyncratic use of language, and for the supple gymnastics of a mind that exercises the mind of the reader is being squandered on regimens of trash and semi-trash, taught for reasons that have nothing to do with how well a book is written. In fact, less and less attention is being paid to what has been written, let alone how; it's become a rarity for a teacher to suggest that a book might be a work of art composed of words and sentences, or that the choice of these words and sentences can inform and delight us."

Her essay inspired me to try to teach Hawthorne as a work of art, with vivid language, rather than as a book only to teach author's use of symbolism or to discuss the ways the view of sin has changed in America since the 17th century. Due to the huge number of copies of the Scarlet Letter we had in our book room, my department head gave me permission to allow my students to write and annotate in their school copies; I encouraged them to circle vocabulary they didn't understand, draw pictures where imagery stood out, and underline particularly powerful lines. We did our Hawthorne Madlibs exercise that we did last year, and they loved it.

They started a list of all the different ways Hawthorne describes Hester: adulteress, malefactress, "naughty baggage," hussy...and wondered why English has so many words for a fallen woman. Just in the first two chapters they discovered edifice, ponderous, congenial, inauspicious, solemnity, augur, physiognomies, heathenish, heretofore, personage, rheumatic, ignominy, contrivance, rankle, manifest, flagrant, contumely, preternaturally, and phantasmagoric. We discovered how valuable a religious background is to reading older texts, as words like "iniquity," "sepulcher," "blasphemy," "cloister," and "hypocrisy" came up a lot. Why call someone an old woman when you could say, "a hard-featured dame of fifty," "an autumnal matron," "the most iron-visaged of the old dames" or "another female, the ugliest as well as the most pitiless"? When Rev. Dimmesdale whips himself and fasts to the point where he hallucinates, rather than have a discussion on if he should have felt as guilty as he did - which we did last year, and obviously they all said, "No" - we discussed how his guilt may have led him to that path, and whether or not his seeking penance was accompanied by an repentance. Instead of asking why Chillingworth was so mean, we analyzed the double meaning of his dialogues with Dimmesdale. Sure, Nathaniel Hawthorne got paid by the word, as one of our English teachers loves reminding me, but the words he wrote are so beautiful and dense and descriptive. I tried to communicate that to my students. I tried desperately to show them how an author can pack all five senses into one sentence (even a really long one), and how our top-sellers today can't hold a candle to the control Hawthorne had over the English language.

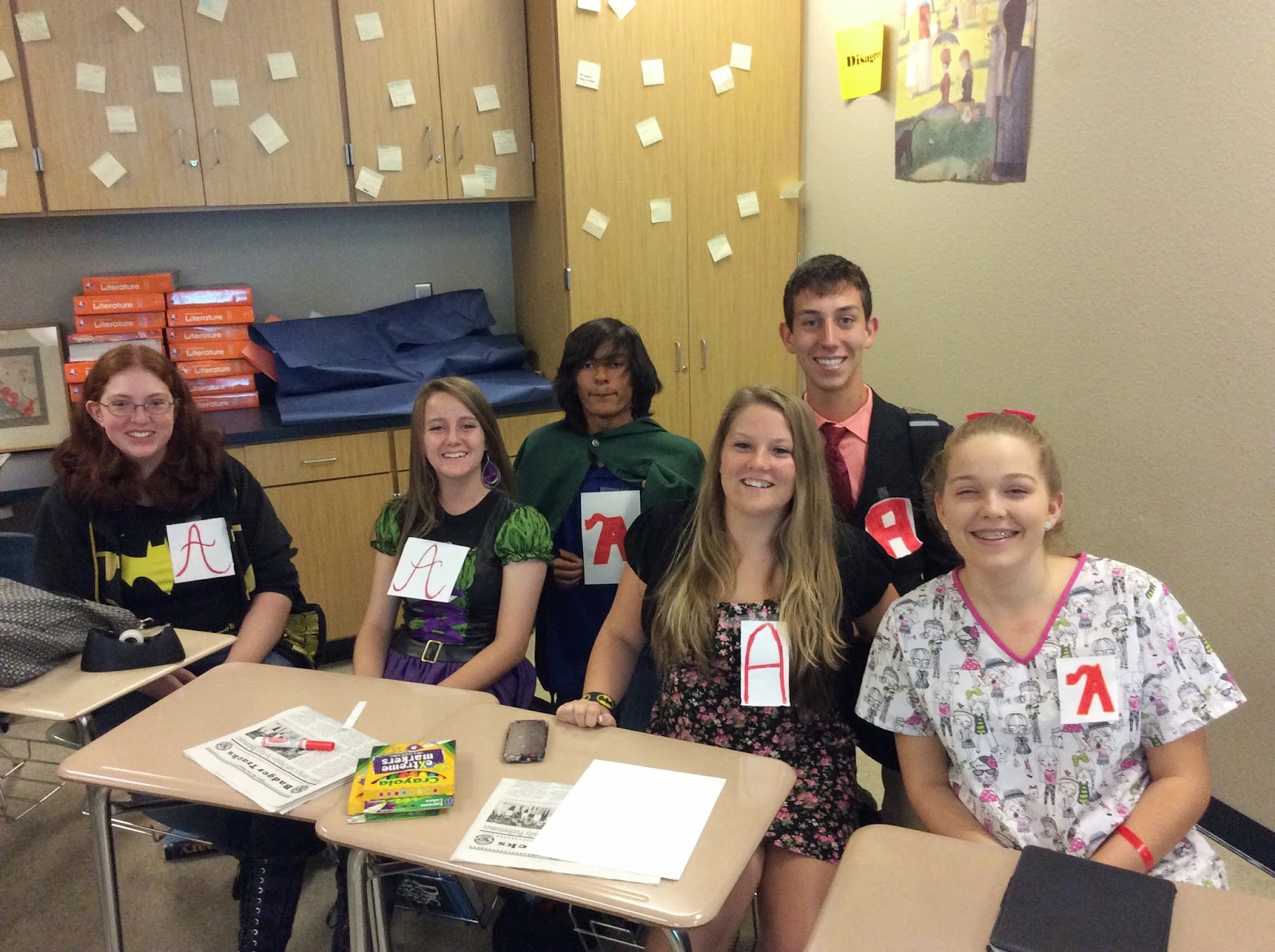

As they wrapped up the book this week, to my pleasure, I got much better feedback than last year. I can't say that every student read every word, but some took off running, and all participated valiantly in the discussions and analysis. One student came in last week and told me I'd been informally voted "most likely to start at cult." When I asked why, he showed me this picture:

Apparently this is what my students do in the back of the room. My students were devastated to find out Hester was buried next to Dimmesdale, but "with a space in between, as if the dust of the two sleepers had no right to mingle." In fact, this unfinished sketch showed up on the back of a reading quiz:

Their prompt for their final essay:

Heard in 6th period while they were discussing which character they were going to choose:

"I'm doing Hester. Hester's easy."

"Well yeah she is...hence the scarlet letter."

Instead of linking the novel with The Crucible like I did last year because of the historical setting, the students read and discussed Francine Prose's essay, "I Know Why the Caged Bird Cannot Read" (Harper's Magazine, 1999). Prose decries the practice of teaching what she perceives to be "simplistic" or "easy" texts to English students, books that have characters that are easy to identify with or that only teach morals, books that have value because the author is black, or grew up poor, etc. rather than for the writing itself. She succinctly writes, "Given the fact that these early encounters with literature [in high school English classrooms] leave such indelible impressions, it would seem doubly important to make sure that high school students are actually reading literature. Yet every opportunity to instill adolescents with a lifelong affinity for narrative, for the ways in which the vision of an artist can percolate through an idiosyncratic use of language, and for the supple gymnastics of a mind that exercises the mind of the reader is being squandered on regimens of trash and semi-trash, taught for reasons that have nothing to do with how well a book is written. In fact, less and less attention is being paid to what has been written, let alone how; it's become a rarity for a teacher to suggest that a book might be a work of art composed of words and sentences, or that the choice of these words and sentences can inform and delight us."

Her essay inspired me to try to teach Hawthorne as a work of art, with vivid language, rather than as a book only to teach author's use of symbolism or to discuss the ways the view of sin has changed in America since the 17th century. Due to the huge number of copies of the Scarlet Letter we had in our book room, my department head gave me permission to allow my students to write and annotate in their school copies; I encouraged them to circle vocabulary they didn't understand, draw pictures where imagery stood out, and underline particularly powerful lines. We did our Hawthorne Madlibs exercise that we did last year, and they loved it.

They started a list of all the different ways Hawthorne describes Hester: adulteress, malefactress, "naughty baggage," hussy...and wondered why English has so many words for a fallen woman. Just in the first two chapters they discovered edifice, ponderous, congenial, inauspicious, solemnity, augur, physiognomies, heathenish, heretofore, personage, rheumatic, ignominy, contrivance, rankle, manifest, flagrant, contumely, preternaturally, and phantasmagoric. We discovered how valuable a religious background is to reading older texts, as words like "iniquity," "sepulcher," "blasphemy," "cloister," and "hypocrisy" came up a lot. Why call someone an old woman when you could say, "a hard-featured dame of fifty," "an autumnal matron," "the most iron-visaged of the old dames" or "another female, the ugliest as well as the most pitiless"? When Rev. Dimmesdale whips himself and fasts to the point where he hallucinates, rather than have a discussion on if he should have felt as guilty as he did - which we did last year, and obviously they all said, "No" - we discussed how his guilt may have led him to that path, and whether or not his seeking penance was accompanied by an repentance. Instead of asking why Chillingworth was so mean, we analyzed the double meaning of his dialogues with Dimmesdale. Sure, Nathaniel Hawthorne got paid by the word, as one of our English teachers loves reminding me, but the words he wrote are so beautiful and dense and descriptive. I tried to communicate that to my students. I tried desperately to show them how an author can pack all five senses into one sentence (even a really long one), and how our top-sellers today can't hold a candle to the control Hawthorne had over the English language.

As they wrapped up the book this week, to my pleasure, I got much better feedback than last year. I can't say that every student read every word, but some took off running, and all participated valiantly in the discussions and analysis. One student came in last week and told me I'd been informally voted "most likely to start at cult." When I asked why, he showed me this picture:

Apparently this is what my students do in the back of the room. My students were devastated to find out Hester was buried next to Dimmesdale, but "with a space in between, as if the dust of the two sleepers had no right to mingle." In fact, this unfinished sketch showed up on the back of a reading quiz:

Their prompt for their final essay:

In many novels, the author presents a character in whom there is a correlation between that character’s physical appearance and his or her mental, emotional, or moral state. Choose one of the characters in The Scarlet Letter: Hester Prynne, Roger Chillingworth, Pearl, or Arthur Dimmesdale. Write an essay discussing Nathaniel Hawthorne’s presentation of such a character and how this correspondence between the physical and mental aspects of the character are related to the significant themes of the novel.

Heard in 6th period while they were discussing which character they were going to choose:

"I'm doing Hester. Hester's easy."

"Well yeah she is...hence the scarlet letter."

Comments

Post a Comment